According to sociologist Gretchen Sisson, the adoption industry in the United States is based on one inconvenient truth. “For every family that is formed by adoption, you have a family that’s separated by adoption,” she says. But the narratives that dominate our understanding of adoption advance the idea that the process is inherently good for everyone involved, reducing the role of birth mothers to the decision to give their child up so that they can have “a better life,” if the perspective of the birth mother is even represented at all. Stories of separation — of the circumstances that lead a mother to relinquish her child in the first place and of the grief she experiences as a result — are often erased from the public record.

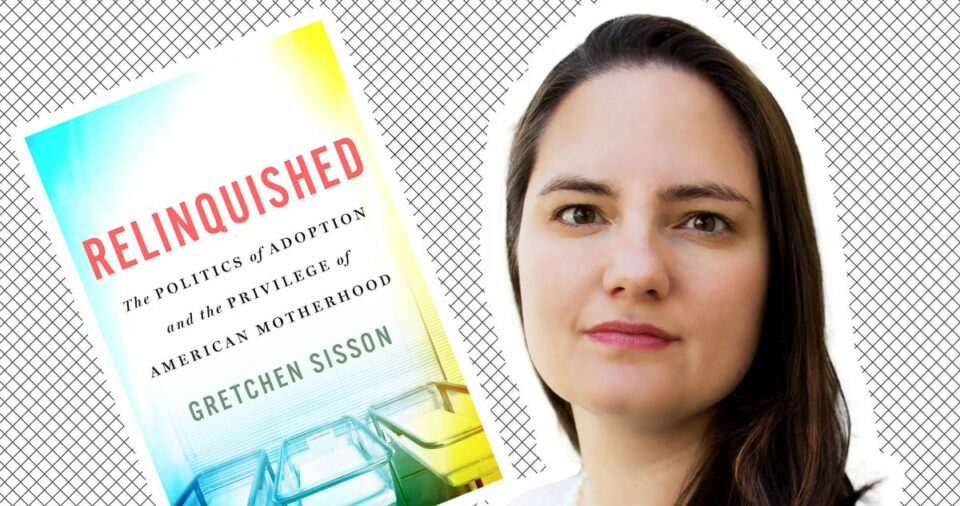

Sisson’s new book, Relinquished: The Politics of Adoption and the Privilege of American Motherhood, out now, seeks to correct this disparity. Sisson is a qualitative sociologist at the University of California San Francisco, where she focuses on adoption, abortion, and pregnancy decision-making. She interviewed more than 100 women who placed their infants for domestic adoption in the United States between 2000 and 2020, compiling these mothers’ stories to challenge the feel-good narratives that persist around the industry. “Everyone loves adoption, right? If there’s one thing that our elected officials can agree on in a robust policy way, in a bipartisan way, is that we support adoption,” she tells the Cut. “But it’s worth considering what that means, what that looks like for the people who are actually living it.”

What made you interested in adoption?

My work has always been in the area of reproductive health and justice. Adoption felt like a missing piece that we haven’t examined that closely, as far as what it actually means for mothers who relinquish their infants. A lot of it was inspired by my work in abortion access, culture change around abortion, and my work with young mothers — particularly teen moms and looking at the ways that their parenthood has been stigmatized and marginalized. When I first started working on this book, I was still in graduate school and I had done my master’s thesis on couples that were experiencing infertility. It was clear to me that adoption was understood as this recurring panacea for all these issues — if you support and promote adoption, then you don’t need to have access to abortion. You don’t need to support vulnerable families. You don’t need to ensure that health insurance is covering infertility treatments and other ways of family building. That made me want to look at it more carefully and see how the actual experiences of the people behind adoption reflected this social and cultural idea that we have of it.

One of the things I loved about the book is that it centered women who relinquished their children, rather than adoptive parents or adoptees themselves. That’s a perspective we rarely hear about.

As I started doing this research, it became clear to me that there’s this tremendous gap among our social, cultural, and political ideas about adoption and what adoption is actually like for those people who are living it — what it means for both the mothers and their children over the course of the rest of their lives. I was incredibly moved by their stories. I found them compelling, both as a social scientist and also as a person and as a mother. I also think that their own words are more resonant than almost anything I could write. The book was in a lot of ways inspired by Ann Fessler’s The Girls Who Went Away, which is about birth, motherhood, and adoption relinquishment before Roe v. Wade. I found the way Anne incorporated those first-person narratives between her chapters very powerful.

You mentioned that adoption is seen as a panacea. What do you mean by that?

A lot of people with power in our society, whether that be political power or cultural power, are people who are closely tied to the families that are formed by adoption. You have a lot of adoptive parents in elected office across the country. I don’t know of any — though I’m sure there are — birth parents who are vocal about their experience in that position. A lot of how we understand adoption is shaped by adoptive families and people who know them well. That is a big difference. For every family that is formed by adoption, you have a family that’s separated by adoption. Their stories are largely erased and absent from these broader political and social conversations.

That is a power dynamic that we see shaping how we understand adoption broadly. One of the things that surprises people most is when I talk about how the vast majority of mothers whom I interviewed wanted to parent. They continued their pregnancies intending to parent, and it was largely a function of money that prevented them from doing so. They’d be like, “I just needed a safe apartment,” or “I just need to get a better job,” or “I just need to be able to have a car.” We have to understand adoption largely as a product of inequity and poverty, and that is a fundamental understanding that we just don’t have in this country.

People in power, such as Justices Amy Coney Barrett and Samuel Alito, have pushed the idea that because adoption is available, there’s no need for the right to abortion. But the statistics disagree: There are about 1 million abortions every year, while only about 19,000 women relinquish their children. Why does this narrative persist?

Of the women I’ve interviewed, almost none were choosing between abortion and adoption. Most of them wanted to parent. Which isn’t to say that there weren’t women who considered both abortion and adoption at different points in their pregnancies. But a lot of them were not able to get an abortion. They were denied access either because they couldn’t afford one, providers were too far, or they were past gestational limits.

So, why does this narrative persist that women are choosing between abortion and adoption? There are a couple reasons. One is that we don’t want to acknowledge that abortion bans are an imposition of motherhood. We want to believe that people still have choice and free will, even when they don’t have access to abortion. We give them this out around adoption like, “You can just choose this and this isn’t going to impact your life that meaningfully if you take this path.” That’s not what we found at all. These women’s lives are hugely shaped by their adoption. It mirrors this conservative idea of how we don’t just want to prevent people from having abortions, but we also have specific ideas of what families should look like. This regressive, heteronormative idea of a two-parent married family that is middle class is still the aspirational goal, and it means that we don’t have to support vulnerable families. We don’t have to acknowledge that a lot of the women who are going to be parenting as a result of abortion bans are going to be parenting in poverty, and that it is going to require state investment to help take care of them and their families. What we want to do is transfer children from vulnerable and poor families to middle-class families and then say, “Problem solved!”

That plays into one theme that kept coming up among a lot of the women whom you interviewed — they believed they were “giving a better life to their children” by giving them up.

I followed many of these mothers for ten years. I have a wider view of their lives. Many of them had more children not that long after the adoptions. That doesn’t even include the women who were already parenting children at the time of the adoption. I point to one example in the book of a mother who had three older children whom she raised. She had a new baby, she had lost her co-parent for her older children, and she went through postpartum psychosis. She had to relinquish that child because she didn’t feel that she could keep them safe. When I interviewed her a few years after the adoption, she was with a new partner, she was expecting again, and she had a plan for support if she had a mental-health crisis after that baby was born. She wasn’t a uniquely incapable mother. She was raising three children. She was excited to be pregnant again and raise this baby. It was just that she had this crisis at a time that she was especially low on support and couldn’t put the pieces together to make sure that she could keep herself and her child safe.

One woman I interviewed believed that she was giving her child a better life. She grew up in the Evangelical church. That was the defining characteristic of her social circle, her life, and her understanding of herself. She adhered to this idea that by giving her child to married parents — middle-class parents who were successful — that she was giving him a better life. When I spoke with her again a decade later, her son had some challenges. He was neurodiverse, he had autism, and she watched his adoptive parents struggle with understanding how to support him and who he was. They had an open adoption. She was in contact with him, she had married at that point, and she felt that she and her husband at that time were able to be a lot more patient with their son, and that her current husband would’ve been a great stepfather to her child because he had similar neurodiversities. She felt that she had given her child up under this better life idea, but that her home would’ve been a better place for him in the long run.

One recurring theme throughout the book is that the adoption system is coercive. Even in the best-case scenarios, relinquishing mothers received very little information about their rights or the impact that adoption may have on their kids. The papers to terminate parental rights were signed within hours of giving birth, when people are just starting to recover. Do you think it is possible for adoption to eliminate coercion entirely?

Asking questions about what ethical practices and less harmful policies could be is a worthy conversation. What does it look like to ensure that meaningful and unbiased options of counseling are provided to everyone who’s interacting with an adoption agency? Who are we allowing to market adoption? What does it mean to do pre-birth matching between adoptive families, prospective adoptive families, and expectant people who are considering adoption — does that confer a sense of obligation? It’s worth thinking about ways that we could make the system more protective and more thoughtful. But those aren’t the questions that excite me the most. As a researcher and as someone who believes in reproductive justice, I am far more interested in what it takes to support families to stay together. I believe that that is what the vast majority of women whom I spoke with wanted.

The policies that would allow families to stay together are the same policies that we think about when we think about supporting American families broadly: the child-tax credit, access to affordable child care, universal pre-K, living-wage jobs. For families that are vulnerable, food subsidies and housing vouchers, as well as other social services such as addiction treatment and meaningful health care, make it easier for people to get through crises and feel like they can make it work.

One woman you interviewed told you that she did not want to resent that her child’s adoptive family was only possible because of her own heartbreak. What did you find in your interviews when it came to regret and grief?

Soon after the adoption, there’s a sense of loss and mourning that comes from being separated from a child — that was pretty true across the board. Some mothers, once you get a little bit out from that mourning period, went into what a couple of them called the “rainbows and sunshine” or “adoption honeymoon” period. This is a time where they felt optimistic: They have an open adoption and it’s going to be great. Usually they are somewhat still in the phase of life that they were in when they made the adoption decision. If they relinquish their child because they were a poor college student and couldn’t figure out how to make it work, they’re probably still a poor college student. If they relinquished because they were deep in the Evangelical church and they adhered to those worldviews, they’re still there. They haven’t moved that far from the person who they were. The decision still makes sense to them.

But a lot of them, once they got further out, became more critical. A lot of them found new partners; many of them got married, had more children. They were in a more stable place and started to question things like, “Well, for two, three, four, five years it would’ve been tough to parent under those circumstances. But could I have gotten through that?” The open-adoption relationships that a lot of them were in became challenging. Some became hostile or closed. These relationships are complicated. They are still a social rarity and they’re hard to maintain. These mothers were feeling like they had been misled about what this would look like long term. When I interviewed them ten years later, no mothers were happier than when I interviewed them before. A lot of the promise of adoption, what they are told to expect for themselves and their child, doesn’t reflect the reality of how it plays out over the course of their and their child’s lives.

Few of them said, unequivocally, “I regret this adoption.” When I would ask, “Do you wish you’d made a different choice?” I was asking them to choose between two different lives. One woman I interviewed had gotten married and had another daughter. She said, “I don’t know if I parented my first child, if I would be married to this man, if I would have this child whom I have.” It was hard for her to say, “I regret that adoption,” because she loves her partner and she loves the child whom she has now. But what she did say is, “I do wish I could have all my children with me.”

This interview has been edited and condensed for length and clarity.

Andrea González-Ramírez , 2024-02-27 14:00:06

Source link